Architectural Drawings Catalogues in the Digital Age

Tom Drysdale, Archivist, Historic Royal Palaces

A card catalogue at the Bodleian Law Library, 1964 (John Donat/RIBA Collections)

A fundamental question to ask when considering the nexus between architectural archives and their audiences is: how should access be provided to items in the archive?

For many researchers, catalogues are the first point of contact between the user and the object of their research. They serve as a gateway to discovery, a provider of contextual information, and the starting point for further research.

A subset of archival catalogues is the architectural drawings catalogue. These have taken many forms. The earliest, created in the first half of the twentieth century, were written in manuscript or typewritten, and were available only in the search room. Printed catalogues appeared in the 1960s. In this format, the RIBA set the benchmark with the publication of its catalogue, under the general editorship of Jill Lever, in 21 volumes. Nowadays architectural drawings catalogues tend to be created in virtual form and are usually published online with few appearing in print, save for the occasional catalogue raisonné.

The RIBA Drawings Catalogue, published between 1969 and 1984, opened up the RIBA’s collections to a wider audience and pioneered architectural drawings cataloguing in the UK © George Jeffery Books

Two distinct approaches to cataloguing architectural drawings are discernible. The first, pioneered by the RIBA, can be termed the ‘art-historical’ approach. Its characteristics are an emphasis on the physical and aesthetic qualities of drawings, while priority is given to physical description and attribution over the establishment of provenance and intellectual control.

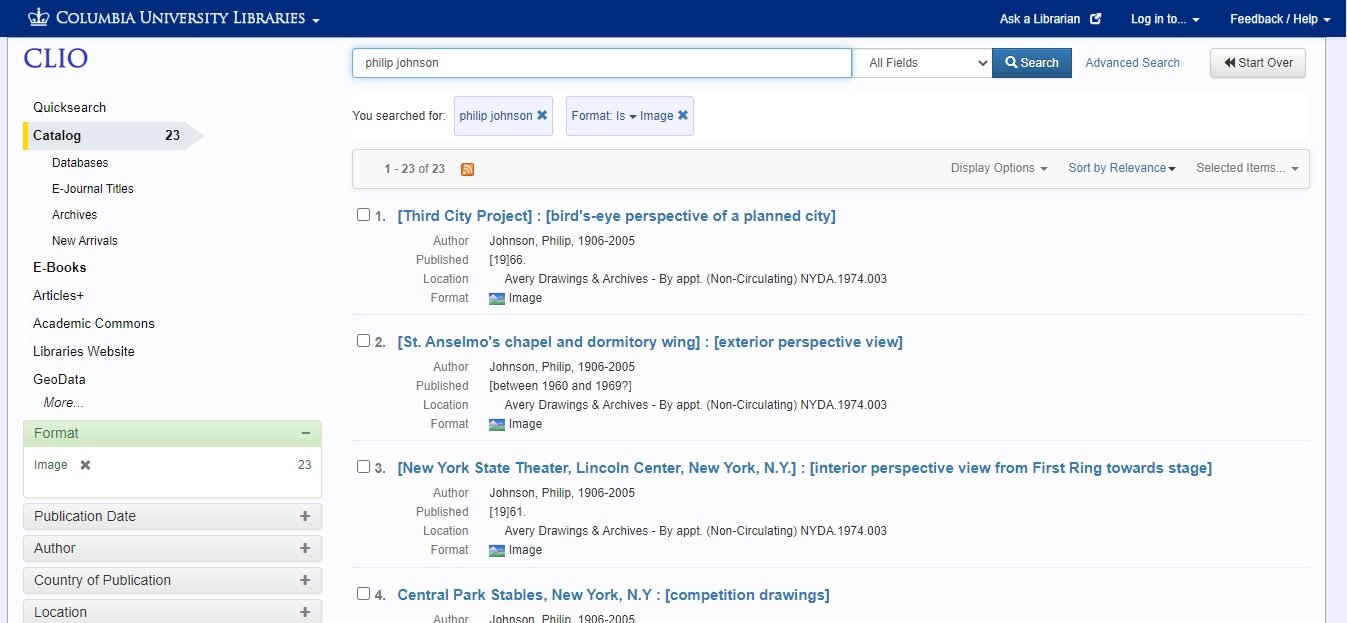

The second approach is related to the use of bibliographic systems and standards in libraries and manuscript collections, particularly in the United States. The bibliographic approach typically involves encoding descriptions using the MARC standard, resulting in the creation of catalogues with limited hierarchical structure.

A bibliographic catalogue including drawings by Philip Johnson at the Columbia University Archives

In the age of the Internet, automation and portable technology, however, cataloguers have been slow to adapt. The cart has been put before the horse; or rather, before the self-driving electric car. Instead of forging new practices that exploit the possibilities of digital technology, cataloguers have been largely content to transpose the practices of the pre-digital era.

This is not to disparage the traditional approaches. The catalogue raisonné – by nature a work of scholarship – has its place. Many are invaluable for those researchers whose interests encompass the intellectual archaeology of buildings, and for proponents of the craft of architectural drawing. But it would be remiss to assume that the needs of users today are the same as those of researchers working in the pre-digital age.

What, then, are the opportunities that technology offers for the creators and users of architectural drawings catalogues?

The first is synonymous with the rise of the Internet. Web technology has enabled the permeation of information and networking on a hitherto unimaginable scale. Information sources are available to a vast audience on a range of devices and platforms thanks to the World Wide Web. Furthermore, web technology allows information to be created, shared and manipulated in a raft of ways. In such a connected world, interoperability is key. For cataloguers, this means that adherence to widely-used standards for the structure and content of data must become a necessity.

The mass availability of catalogue information has vastly increased the potential audience for descriptions of architectural collections. Today’s researchers are more likely to encounter the objects of their research via the interface of the catalogue than the physical space of the search room. But this new arena of interaction has created new expectations for users around access. Consequently, the challenge of understanding the needs of the audience for archives has become more vital than ever.

Sites such as HistoryPin use interactive map-based interfaces to help users retrieve information

Of course, technology also provides the cataloguer with a host of new tools for eliciting engagement with collections. Faceted search features and visual interfaces provide new, user-friendly routes into collections. At the same time, the potential for greater user engagement – a key feature of the 21st century web environment – means that users can now participate in the cataloguing process through the medium of tagging tools, comment boxes, wikis and the creation of folksonomies.

Finally, the proliferation of born-digital designs poses distinct challenges to the fundamental theory and principle of archival arrangement and description. Contrary to the principle that records should be arranged according to their ‘original order’, archivists must question whether flexible arrangements might not better reflect the realities in which digital design records are created and used. Simultaneously, the practice of describing drawings at the level of the individual item is likely to become an unrealisable aim unless traditional methods are combined with technological solutions such as the automated capture of metadata.

It is only by putting the available technology first, rather than continuing to force information into the moulds of practices arising from the print era, that catalogues will be able to serve modern users in a way that meets their needs and expectations.