THE DOORSTEP

Sharaye Campbell

My final year dissertation titled ‘The Doorstep’ looked to investigate how the domestic interiors of my family members homes constituted to an archive of the Black Atlantic. Initially starting as a means of unravelling stories of my family’s voyages, I researched how the routes they took, and the spaces they occupied changed their outlooks. The writing then began to focus more directly on my maternal and paternal grandparents’ journey from Jamaica to their home in Britain and how each stage in this journey acted as a threshold.

This piece is part of the Race+Ethnicity Network blog post series.

By analysing spaces at different scales, I identified the contrast of residing in rural Jamaica to urban spaces in the UK. I dissected specific waves of immigration, before focusing on Handsworth, Birmingham, the place my grandparents called home.

Revolving around the central themes of social cohesion and inhabited space, a discussion formed concerning the factors that influenced the migrant communities. This reviewed the connections to economics, class, and education through the study of intersectionality. I examined possible links between a family’s income, their sociopolitical identities and how physical manifestations of social isolation appear in the home. This led to further research by relating historical studies to the first-hand accounts of my grandparents and extended family, looking at both the micro and macro events that have affected the homes they grew up in.

In looking at the corresponding effects of social isolation on migrant communities and the spaces they inhabit, I began to understand more about their reasoning for immigrating to the UK as well identifying the factors that contributed to both the development and hindrance of these experiences, thereby creating an awareness of past and present migration issues. I also gained further insight into the current UK migration crisis which has resulted in marginalised areas.

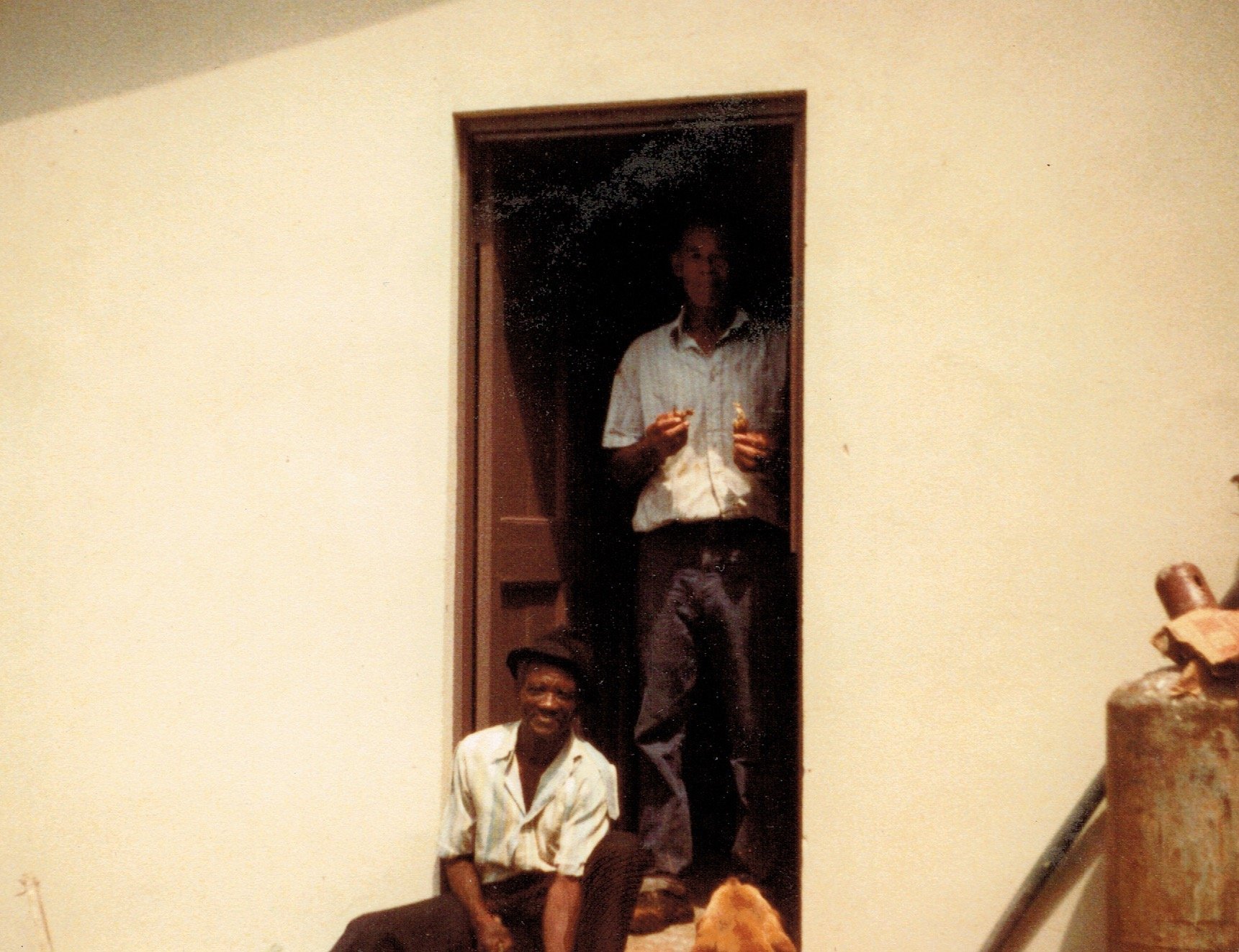

These studies also emphasised some interesting statistics regarding the importance of climate and its contribution to the blurring of boundaries between the indoor and outdoor areas in Jamaica. The climatic shock of an English winter altered the conventional spacial traditions of many West Indian families, the division between public and private was much more rigorous in the UK than in Jamaica as they were transposed into a very different way of living.

It was also noted that the inability to form relationships in certain environments, as well as factors, such as climate and a country’s economy can cause certain cultural preferences to conjugate. The West Indian people came together in Birmingham and isolated themselves to build a community and to feel secure, highlighting the solidarity, strength and unity formed as a collective.

I uncovered information about people and places, which enhanced my awareness of the huge impact the small Caribbean island of Jamaica had on so many people, not just in the UK but on a transatlantic scale. The encounters through space and time moulded my Grandparents, just like the many other brave women and men that chose to take their faith, ambition and a small suitcase across the seas to better themselves and create an environment free of hardship for the future generations.

On arrival to Britain in the 1950s, West Indians’ were often refused accommodation and left with no other choice but to live in contained, cramped rooms, often occupied by other West Indian immigrants. The threshold of privacy was broken in these situations, leading to an intimate and unspoken support system between these newly formed families. Eventually, ‘The Race Relations Act’ came into force in 1968. It was an Act of the Parliament in the United Kingdom making it illegal to refuse housing, employment, or public services to a person on the grounds of colour, race, ethnic or national origins.

The studies of material culture are analysed throughout the writing as one of the key forms of self-expression for the communities of the Caribbean diaspora. By studying the psychology of interiors and its effects on human behaviour, I observed how migrants would create interior spaces in the UK home based on memories of their homeland. The use of material objects as cultural survival is seen in the case of the Caribbean diaspora who migrated to the UK. It was certainly evident in their dialect, traditional clothing and within their homes. For example, cast iron dutch pots that were traditionally used in Jamaican kitchens, became a staple kitchen appliance in the British home.

Through the findings above, it is clear that social isolation led to the strengthening and rooting of the Caribbean community, allowing them, to this day, to still keep their traditions, whether that was through material culture or skills that they were taught back home.

Events such as weddings and birthdays are examples of moments in time where the social discrimination faced by my Caribbean family encouraged a wholesome community affair where houses became homes and underground parties began to form and grow. Churches became the home, and the home became the church, wedding receptions were in living rooms and cousins, aunties, and uncles saw your abode as an extension of theirs. It was a hybrid of living and it made the community stronger.

Certain ‘lived experiences’ changed depending on the generation. With the attitudes and apprehensiveness of my grandparents becoming less apparent in their offspring and how they navigated through life in Britain. Initially, the social isolation of the West Indian community was seen as an inevitable and normal aspect of setting up a new life in the UK. Certain racial biases were significantly detrimental, restricting work opportunities and the type of spaces that could be inhabited. The West Indian community formed their own spaces and financial systems, such as the pardner, which allowed them to grow and have trust in each other, paving the way for future generations, such as my parents and myself. This could then disperse wider into the communities without apprehension or peril.

It was clear from these stories that a series of implicit and explicit factors, much deeper than just socioeconomics, played an important role amongst the West Indian community. These stories revealed the sacrifices made by the first generation so that future generations could have a brighter and prosperous future. It was a sacrifice that was made for the generations after them in hope that their struggles would not be as hard. The united strength of the culture, can be seen today in shop windows, music, language and the health services to name but a few.

Sharaye Campbell

a Master of Architecture graduate from the University of Westminster, discusses the findings of her 5th year dissertation titled “The Doorstep.”

LinkedIn: Sharaye Campbell

Instagram: scarchitecture